On Untangling Trauma Threads, Part One

what the fuck: the lengthy process of trauma healing is exhausting but it's working

When people claim wholeness,

I wonder if I’ll ever get there.

It’s no secret that I’m working on untangling and examining trauma threads. Through copious journalling and self-reflection, under the guise of isolation and recovery, I realised that part of me felt disjointed and disconnected. I no longer feel sensations in my body that could show emotionality—or, at the very least, I’m out of touch with feelings. In our therapy sessions, my psychologist challenges my existing concepts of attachment by pointing out the obvious, insecure foundations. And she’s urging me to release emotions that my inner child wouldn’t dare. In fact, I needed to take more psychological assessments because, well, there are so many threads fraying in the tapestry that form my relational foundation that we can’t discern where to start.

As an adult, I made the pointed choice to keep an entire country and part of an ocean’s distance between myself and my caregivers because it’s healthiest for me. I know some of my friends choose to cut theirs off and go no contact, and often my choice to put some space between the people who raised me has come with similar questions as the ones on estranged parents’ forums. It’s funny because I love my parents, I really do, but I can also acknowledge how they raised me was not the healthiest. The ways they show love (mostly resourcing) are often incompatible with what I need instead: validation, acceptance, and love.

In much of the complex childhood trauma literature, they often correlate (and it makes sense) that the parent-child relationship will later affect that child’s emotional regulation skills. In fact, a 2006 study by Judith Feeney showed parents’ attachment, conflict style and perceptions of conflict will affect and repeat in the child later on in life. Children replicate and repeat patterns of negative conflict modeled by their parents—for example, verbal attacks or avoidance of conflict, as shown in Feeney's examples—leading to feelings of loneliness and dissatisfaction in their relationships, including those with their parents.

As someone who practices a polyamorous relationship style, I have plenty of experience with repeating my parents’ attachment styles when I date someone new. Describing how most of my relationships begin intensely, with a passion that prevents me from seeing compatibility, my friend (who has borderline personality disorder) asked if I'd ever been diagnosed with BPD. I feel safe enough with that person to laugh and pseudo-pathologize about my relational trauma and this most recent rupture, but there are painful bits of truth lodged in that assessment.

In a 2014 paper, Virginia Goldner presents a hypothetical couple made up of composite traits of some of her couples clients, going in depth to their history. Both parties in the relationship have histories of trauma: divorce, early parental death, and emotionally neglectful and distant caregivers. She goes onto describe that when the couple has conflict, the behaviours mimic borderline personality disorder in its rapid cycling between defensiveness and anxiety. Of course, because this is a composite couple, they represent plenty of couples’ struggle in the therapeutic process. It’s funny because I see myself in the case study, in particular, mimicking the dynamic I had with a former partner.

After last year, a period where I experienced one of the worst break-ups I’ve ever had, I no longer recognised who I was or what I wanted. I could see the end of the relationship after months of insecurity and health struggles on both of our ends. I never felt like I could voice what I needed — and even worse, when I did, we danced around it and it was never the right time — it only made the end more volatile. The funny thing is, just like Goldner’s couple, both of us have a history of relational trauma. For myself, compounded with the medical mystery I was in the middle of unravelling and unpacking of my own developmental traumas, I couldn’t handle it anymore. The insecurities that were already there only heightened. And while we loved each other very much, the flame burned out just as quickly.

It is not my place to air out my ex’s issues, even now, and while I can only speak to my shit — there were signs of incompatibility from the start. First off, the power imbalances: I never considered this to be an issue, but this ate away at them, and like most people I end up seeing, they built up resentment for my abundant resourcing and stable relationship with my spouse. My need for stability amidst a turbulent time turned into a lack of understanding of when they wanted to explore a primary partnership. (All the while, insistent that I “could not be non-hierarchical polyamory with a spouse.”)1

I was unintentionally cruel, too.

A couple months into our relationship, in a moment of hypervigilance, I clocked my then-lover’s perceived distance as a sign they wanted to leave me. Nothing really pre-empted the panic, perhaps them continuing to cancel plans even though we binged on each other the preceding weeks and maybe the anxiety of falling in love with someone who hasn’t quite earned the security that feeling entails.2 I confided in my therapist, my spouse, and anyone else that would listen about my dilemma, with all of them asking: “Why would you want to break up with someone you like?”

Look, I will level with you all. How I want to be in relation to others differs vastly from others. Above all, I strive for complete honesty and transparency, even at the expense of hurt. I felt, and still feel, that addressing any unhappiness and doubts as early as possible in order to process and move forward was the best way to handle things. In almost every partnership at the first signs of distress, I bolt into flight mode and try to get the fuck away from the source of discomfort as much as possible. That routine gets old after a while, especially when you fall for someone who seems so great for you and shares similar ideals. Noticing this pattern, I told my therapist about how much I wanted to break that pattern — but I didn’t know if it was a trauma response/repeated unhealthy pattern of mine or if the instinct to run was valid and grounded in reality. I actually, very often in this relationship, could not discern how I felt. I was often so full of love and joy whenever I was with my partner, but when I wasn’t — I shrunk down, tried to vie for attention and became confused when they balked at my incredibly puppy-like admiration.

I thought, in that moment of clarity, that telling my then-partner of my insecure attachment patterns, that I was on the verge of ruining almost everything because I panicked, but LOOK! I am here and staying and I love you! My voice pleaded with more desperation as I noticed my partner slowly devolve into a state of dissociation and anxiety. “Why would you tell me that?” Their tone inflected a pain I hadn’t heard before, hanging out in the far reaches of their register. As I reached out to touch them, as a bid for connection, they quickly pulled away, curling up into a ball and drawing their hoodie to a close. “Because I’m here telling you about it. I have this pattern, it’s an insecurity and panic response of mine, but I fought it. There was no logical reason for me to break up with you or anyone else I’m seeing.” I pause, omitting the fact that their inconsistent behaviour mostly targeted this freak out, but clearly they could not handle it if they handled, this, the more innocuous admission this poorly. Met with a stare of disbelief, I continued to explain, “This is really difficult for me to be vulnerable, but I believe in being honest and transparent. I like you a lot, and I freaked out and I thought it would bring us closer if you knew that about me.”

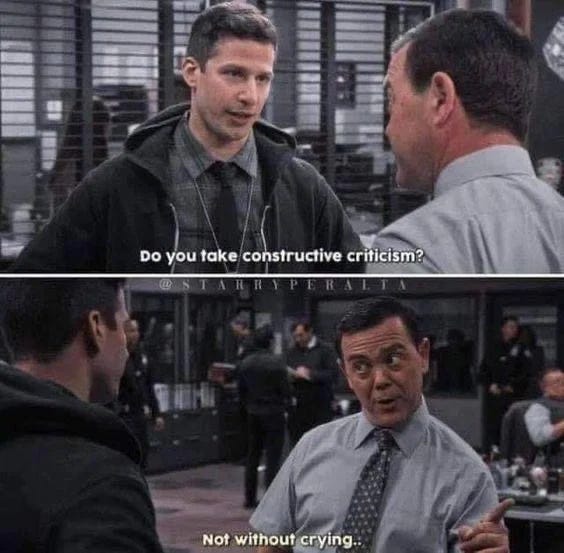

Before moving into forgiveness, they had to get one last snap in: “Well, there are some things you shouldn’t tell people. You don’t have to tell everyone everything. Think about it first.”

It turns out that one of the best cures for complex post-traumatic stress disorder (c-PTSD) is practicing healthy relationships. Meaning, in order to heal from relational trauma, one must learn to break past those fears in order to learn how to healthily relate to others (breaking patterns!) This feels like an impossible feat for someone who is unaware of their own trauma — or rather, has an avoidant coping mechanism and refuses to hear issues without sharpening their defenses.

A couple months before our relationship ended, one of my ex’s best friends sold them out. “[x] was mad in love with you at that point. After the first date, bro! [x] was SMITTEN!” Pushing the friend away and dismissing them, my ex shrugged it off as we went on a different subway line. “Were you really in love with me after our first date?” I asked with a teasing lilt. They evade answering.

Later on, during the Great Catharsis, my ex will cry out in frustration, “I don’t know you anymore! Who is this person? I fell in love with you after our first date, dude! This is not the person I fell in love with!” In response, I will eventually dissociate into hysterical fits of crying, hours-long floats3, and every time they try to touch me, my body will tense up, freeze and recoil.

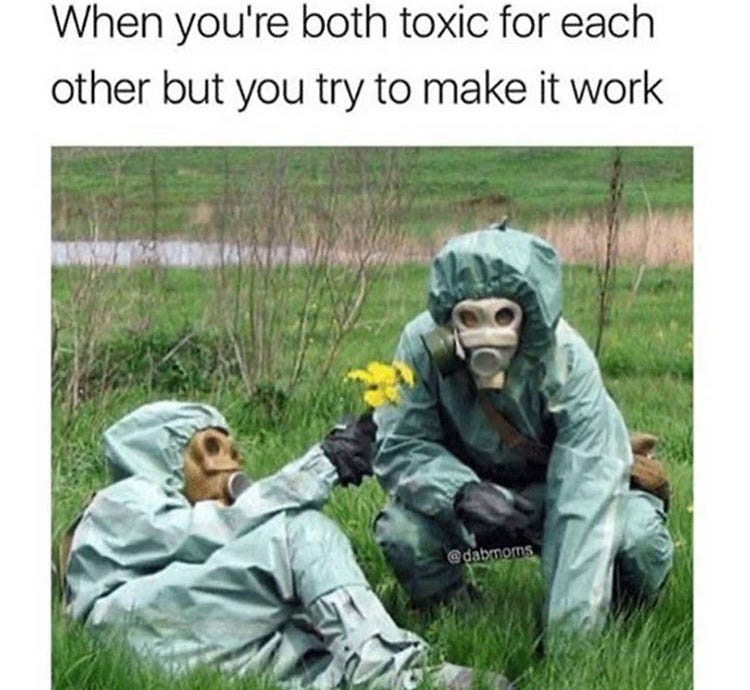

These patterns of behavior don’t materialize out of nowhere. Clearly, they are often the ghostly echoes of childhood trauma, reverberating through adulthood. Research supports what many of us already know in our bones: that cPTSD, shaped by inconsistent care, neglect, or relational instability, directly correlates with the unhealthy dynamics that mimic toxicity (even without tipping fully into abuse.) The hypervigilance we developed as kids, the learned silence and desperation to secure love however we could—all of it shapes how we fight, flee, or fawn when intimacy feels like a trap.

Sure, trauma leaves its imprint on the nervous system... but it also weaves itself into the emotional fabric of interpersonal connections. What looks like romantic dysfunction from the outside can trace back to patterns of survival built long before we could name them. And when those trauma threads entangle with someone else’s? The result can feel like two anxious cats cornered, flinching at every perceived threat while yearning for safety and hissing at anyone who passes by.

This essay is just the first pass through these tangled knots. The tapestry isn't done yet—it's fraying in quite a few places, gnarled and twisted in others. In real time, I'll be pulling apart those threads: exploring the ways trauma distorts intimacy, how patterns from childhood reappear like ghosts we avoid, and what it might mean to consciously, painstakingly reweave something new.

I don't know if I'll ever achieve that elusive wholeness others talk about. But maybe the work isn't about mending every fracture or finishing the weave. Maybe it's about understanding the pattern, learning how the threads interlock, and finding courage to try again.

Hey friends.

If you enjoyed this essay, I’d love to hear your thoughts. Share a comment, like, or pass it along to someone who might resonate. Engagement helps more people find these threads of reflection.

I also want to let you know that I'm transitioning paid subscriptions from Substack to my website. I can't, in good conscience, continue to give Substack a commission when they knowingly provide a platform to neo-Nazis and right-wing extremists.

So, if you want to support my work, you can move your paid subscription to a Pay-What-You-Wish patronage directly through my website. You can add a custom amount, and this patronage goes directly to my living expenses and medical care— which is super helpful for me in doing more of this work! You can also do a one-time contribution, give a weekly contribution or monthly (come on, you could give up one cup of coffee for the month and use it on supporting your favourite creator instead!)

There, you'll also find workshops like Cosmos of Care, along with options to book one-on-one support sessions with me.

Thanks for being here and supporting my work.

¡Hasta próxima!

C x

Not going to lie, I’m still angry about this. This is an example of prescriptive vs. descriptive language. I now tell people I strive to practice non-hierarchical polyamory, but understanding of the fact that I am married to my most stable and longest partner for the societal benefits.

Alas, we cannot control those feelings. But I now know that is what considered a trauma bond, rather than a healthy one.

I’m actually upset about this too because they commandeered my local float place, but if it helps them, they should do it. I have other forms of self care. I do not want to run into them.